(originally published in the Winter, 1993 issue of Once Upon A Dime)

When Jackson Whitney created Commander Courage, the young artist threw in a lot of his personal obsessions. A dash of patriotism runs through that classic original run, of course, just like many comics of the time. Keeping pace with those early stories is a deep sense of our nation’s history, far more accurately portrayed than most superhero comics of the time, even with a sensationalized (by modern standards) portrayal of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The one aspect of Commander Courage’s world given short shrift would turn out to be the thing that set the character apart from other popular heroes like Captain America, The Shield, and Superman. From the very beginning of the strip, Jackson tried to ensure that his hero represented a deep reverence for nature, just as the Wisconsin autodidact had developed through his own studies.

Pieces of it survived editorial suggestion and outright meddling, as Native American shamans were present at Jefferson Dale’s initial transformation into the buckskinned defender of liberty. There’s some anecdotal evidence that Amazing Comics editor Delmer McNeal wanted the character’s background to be strictly scientific, better reflecting the superiority of American know-how. That jingoistic editorial hand would later bedevil Ken Meehan’s Burning Eye strip, which owed a great debt to Jackson Whitney’s original vision.

Though Jackson took no small pride in the success of Commander Courage, he privately confided to friends that he wished he could do more to lead his young readers down the path to what we would now call conservationism. The occasional nod to Dusty’s Eagle Scout status was not enough.

Sadly, Jackson would never win the battle with McNeal, abandoning the strip after eight months to fight a bigger enemy.

Other writers and artists tried to follow in Jackson’s footsteps, but the results were half-hearted, though certainly entertaining. At worst, these efforts culminated in characters like the “Ancient Indian Imp” (Amazing Comics’ epithet, not mine) Jinxor, who called upon the powers of the Great Spirit to meld animals together in order to cause chaos in general and bedevil Commander Courage and Liberty Lad in particular.

In an incredible feat of irony, the man who had tried to squelch the character’s environmental aspects capitalized upon them to give his company’s image a better coat of paint – bright red, white, and blue with a touch of forest green. To prove Amazing Comics all-American (long after All-American Comics itself had been cancelled), McNeal contacted the USDA Forest Service to offer them the use of Commander Courage.

Foolishly, in hindsight, McNeal promised in a letter that the Forest Service could use Commander Courage at no charge for as long as they liked. Though that offer would later haunt the holders of Amazing Comics’ copyrights, McNeal never saw the results.

At the time, the venerable government agency rejected the desperate editor and publisher out of hand. They already had a character, the stern but loving Smokey Bear.

Originally created in 1944, Smokey had been literally brought to life in 1950 when a bear cub was rescued from a devastating forest fire in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico. Nicknamed Smokey by the firefighters who had rescued him, the cub found a home at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., where he became so popular with schoolchildren that Congress passed a law in order to govern the commercialization of his image. No wonder the Forest Service had no need of a superhero.

However, all things must pass, even anthropomorphized animals. When the “real” Smokey died and was subsequently buried at the historical park that bears his name in New Mexico, the Forest Service found itself at a bit of a loss.

It was 1976. The nation had just celebrated its bicentennial, and perhaps, some in the Forest Service wondered, it was time for a new image.

USDA file clerk George Gemette remembers his part in the brewing controversy. “I was going through some correspondence in the archives when the words ‘Commander Courage’ on a folder caught my eye.”

The portly public servant smiles. “My older brother had given me some Commander Courage comics when I was a kid, but my mom threw them away when I went off to secretarial school. Anyway, I opened the folder and saw the letters between this guy Delmer McNeal and Assistant Chief Edward P. Cliff.”

“If nothing else, I figured that my supervisor might get a kick out of it, so I passed it on up the administrative chain. It was just for laughs. How could I know that (then) Chief (John R.) McGuire had been in boot camp with the guy who created Commander Courage?”

Yes, a chance friendship in 1942 led to great possibilities for Jackson’s “child” thirty-four years later.

McGuire remembered his campmate’s tales of what he would like to do with his character upon his return from war, and realized that he had the perfect opportunity to bring that vision to the nation. Among his proudest accomplishments of the previous year, he allegedly said in a staff meeting in early 1977, McGuire cited the approval of Commander Courage. The comic book hero came second only to McGuire’s role in the National Forest Management Act of 1976, which greatly curtailed rampant clearcutting after local outrage over activity at Monongahela and Bitterroot National Forests.

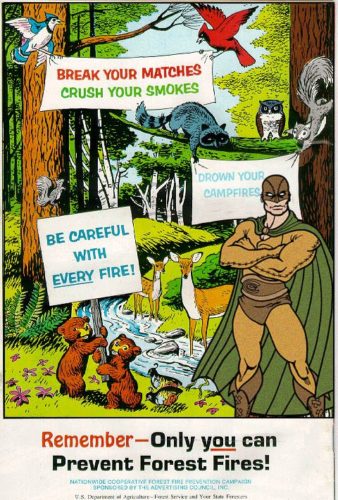

The campaign was to have been simple, beginning with, of course, a comic book, titled Commander Courage Carries On.

In an echo of the classic Commander Courage tale, “Ghost Shaman of Broken Shin,” (Commander Courage Comics #5), an elderly dying bear (specifically not identified as Smokey) would pass his sacred charge on to a worthy human. Having spent his existence ensuring that the essence of Hinoto, a fire elemental, would not rage unchecked, the bear needed someone with both the gentle touch of compassion and the strength of mighty rivers to assume his mantle. Who better to fit the bill than the lame Jefferson Dale and his alter ego, Commander Courage?

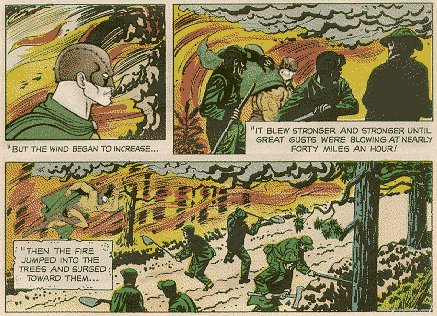

After agreeing to this task, the newly anointed protector of the ecology finds himself pulled toward a forest where careless campers have tossed smoldering cigarette butts near dry underbrush. Soon a conflagration erupts. Not only must the Commander rescue the foolish hippies (no, really – that’s what he calls them, in 1977), but he also aids the smokejumpers who come to battle the flames.

It’s a thrilling 21 pages of story, followed by the obligatory informational games and crossword puzzles so common to this type of comic. For fans in the seventies, it was especially exciting, as this book appeared in that fallow period between the Utopia Squad of the sixties and the First Comics revival in 1982.

Amazing Comics, Ltd., while not actually publishing themselves, took a dimmer view. But as a result of Delmer McNeal’s poorly worded letter (from a legal standpoint), though Amazing owned the Commander, the Forestry Service could still do whatever they wanted with him for as long as they wanted. However, cruel fate would do right by the copyright holders.

The book appeared in National Park gift shops around the country. McGuire had plans for further licensing, and rumor has it that a script was commissioned for a sequel book that would have teamed Commander Courage with Woodsy Owl. However, my research has yet to turn up any evidence of this actually happening.

So why don’t we see Commander Courage as a symbol of American Conservationism today? Well, some of us do. But the simple truth is that the well-meaning McGuire failed to take into account the court of public opinion, barely avoiding actual court.

When the citizens of the Village of Capitan, New Mexico, got wind of the change in Forestry mascots, they were outraged. Their pain over the loss of the actual Smokey, whom they considered one of their own, was too great for this new campaign to happen so soon.

Had McGuire waited a year or two longer, the change might not have stung so much. But he didn’t, and it did. As unofficial Capitan village historian Chris Brital remembers, “we have two claims to fame – Smokey and Billy The Kid. If they’d wanted to replace the Kid, we might not have been so irate.”

The citizenry wrote to their Senator, Harrison Schmitt. Deluged by letters and jars of rancid chiles, the freshman Senator requested a meeting with McGuire. At a closed door session, the two had an apparently friendly discussion over the matter, if you consider the threat of a lawsuit friendly.

In the end, further plans for Commander Courage to supplant the venerable bear were scrapped.

The initial print run of Commander Courage Carries On was allowed to sell through at the parks, but it was agreed that there would be no second printing. Eventually, the USDA Forest Service reprinted The Story of Smokey Bear, and gift shops quietly pretended that the Commander Courage book didn’t exist. (There’s still some argument among Courage fans over whether or not we should consider it canonical. Certainly, the First Comics revival made no reference to it.)

In 1984, the U.S. Postal Service cemented the deal, by issuing a postage stamp depicting a frightened bear cub clinging to a burnt tree, with the Smokey Bear emblem in the background. To date, Commander Courage has not been so honored.

(Once Upon a Dime was a website created in 2003 to tie-in with Mark Hamill’s directorial debut, Comic Book the Movie. Though written by Derek McCaw, this fake history article was originally attributed to Donald Swan, Hamill’s character in the movie. All artwork by Mark Teague.)