The Doctor has lost his best friend. His best friend has forbidden him to take out his anger and grief on anyone else. But he can still take it out on himself.

There’s no mystery as to the subtext here. It’s a labyrinthine prison, containing a literal image of Death as the minotaur pursuing the Doctor through the maze, complete with shroud and flies. The Doctor finds a spade and uses it to dig up what looks like a fresh grave. The castle is empty of any other people, but one room holds a peeling painting of Clara. And at the bottom of the ocean surrounding the prison is a seabed of skulls. We probably don’t need a dream dictionary to figure out these symbols.

And the main action is the Doctor figuring out exactly what he needs to do to race one step ahead of Death, rapidly calculating gravity and time in his head, analyzing mineral hardness and teleport engineering with his sonic sunglasses and Time Lord ingenuity, “winning,” as Clara would put it, by the skin of his teeth. And then the literal punch line: winning in this case involves doing all this over and over and over again, repeating his actions over billions of years, so that he can break down the harder-than-diamond wall in the one room that doesn’t reset itself to its previous state, one frustrated fist at a time.

We were promised in the previous episode that someone had arranged to kidnap him to this place, and we see that he manages to punch his way out of it over billions of years, fulfilling the promise he made in “Day of the Doctor” to reach his home planet of Gallifrey “the long way round.” But we also see that his prison was situated within his confession dial. Apparently a confession dial is like a TARDIS — bigger on the inside — and not only can you be teleported into one, and die within it repeatedly, you can somehow punch your way out of it as well. Maybe in “Hell Bent” we’ll get the rest of the story: who put him in there? were they really interrogating him, and if so, was it really just about the hybrid?

More questions abound. If the creature kills you when it catches you, weren’t the interrogators relying heavily on the Doctor to figure out how to slow it down and to survive long enough to produce the exact confession they wanted? Did the first Doctor to die just remember the “BIRD” story on his own, and figure it all out without any clues the first time through? Is this the first televised Doctor Who story to include the word “arse”?

In the cliffhanger, the Doctor seems to reveal that he himself is the prophesied hybrid. Which of course put me and probably a ton of other classic series fans in mind of the “half human” line from the 1996 TV Movie. It’s crazy to think Moffat might be headed there, and yet it’s just the sort of thing he’d try to make work. And while I’m uneasy about the idea of retconning what to me is a more inspiring and interesting take on the Doctor’s flight from Gallifrey — the implication that Time Lord society was too detached from the rest of the universe and too stagnant to stimulate a mind like the Doctor’s — I’ll reserve judgment until I see what he has in mind. I’ve seen people speculate that he didn’t say “the hybrid is me” but “the hybrid is Me,” which raises all kinds of questions about what he knew this season and when he knew it.

The other classic series bell ringing here is the Matrix, an idea Robert Holmes came up with for the 1976 story “The Deadly Assassin” that was reused in 1986 for “Trial of a Time Lord,” well before the movie of the same name in 1999. The idea is that Time Lord consciousnesses are placed into the Matrix, essentially a vast computer network, when they finally die, so that future Time Lord High Councils can access their memories and intelligence in perpetuity. In this it’s not unlike the Nethersphere in which Missy stored people’s minds in “Dark Water,” and both are a kind of afterlife (Heaven, Hell, take your pick). It’s possible, apparently, to enter the Matrix and even do battle within it, Time Lords dueling with one another using landscapes and weapons dreamed up by their respective minds. It’s not clear whether the confession dial is something similar — did the Doctor somehow unwittingly dream up his tortures himself, or did another Time Lord do it? — but the resemblance is striking.

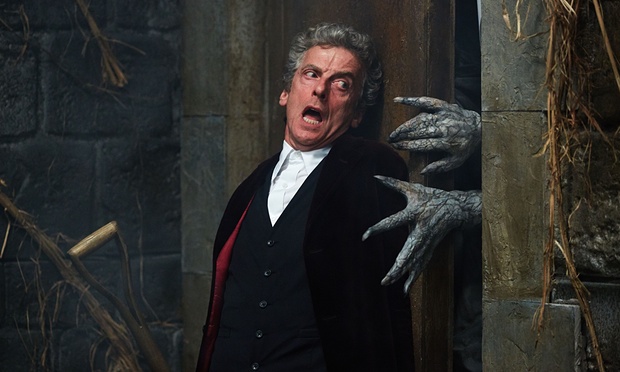

Peter Capaldi, of course, easily keeps this episode compelling all by himself; apart from brief cameos by Clara (her image in his mind, at least) and a Gallifreyan child, the Doctor’s is the only face we see throughout. By now we all know he’s a wonderful actor and good with a monologue. He does scary and determined and clever and agonized very well. Even so, the emotional effect of the episode is a slow burn until the last fifteen minutes, when we discover the Doctor has been living through his own personal and mostly unchanging Groundhog Day, and since Murray Gold’s music gets extremely loud about that time (and just when I was about to give him props for the Paddy Kingsland-esque synth earlier on), it might help to turn closed captioning on so you can actually hear the climactic monologue.

On first viewing, the episode didn’t appeal to me. I think I spent too much time trying to puzzle out what was going on at the literal level, and not enough just relaxing and soaking in the emotional content. On second viewing (with closed captions) it’s much easier to see the very simple and profound thing happening here. At its heart, this is an episode about grieving: repeating what seem like identical, meaningless days doing the same things over and over, seeing reminders of death around every corner, running just to get away from them, hoping against reason that if you just keep doing the mundane everyday things long enough, maybe the person you’ve lost will somehow reappear, knowing there’s no chance it will ever happen…and relying only on their memory to propel you forward to be the person you know they would want you to be.

Fortunately for the Doctor, there is an escape. It’s two billion years in the making, but in the end he can finally crack his own personal prison of grief and come out ready for a fight. He’s one hell of a bird, and now his beak is very very sharp.