Editor’s Note: This article will also appear in slightly different form in the fanzine “Claims Department.”

Channeling the spirit of Frank Frazetta and warping it into something weird and wonderful all his own, comics creator Bernie Wrightson, who passed away last Saturday at the age of 68, left a large mark in the comics industry. By most accounts this master of the macabre was warm, bright and upbeat, a contrast to his talent for illuminating characters with dark secrets and shadows in their hearts.

But then again, maybe that’s not a contrast, because Wrightson’s characters, no matter how monstrous, were so indelibly human. Though his arguably most famous co-creation sprang forth in 1971 – [amazon text=Swamp Thing, written by Len Wein&asin=1401222366] – it was in the 1980s that Wrightson pushed the boundaries of his work, gaining attention outside of the comics industry, and using that attention to push mainstream comics.

In 1983, after years of drawing horror comics – great horror comics – Wrightson released his labor of love — an illustrated version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Done in elaborate pen and ink to simulate the look of woodcuts, the illustrations portrayed a unique vision of Shelley’s characters, taken from her own descriptions in the novel rather than any cinematic interpretation. Published by Marvel Comics, it was a sensation and a heavy influence on artists for years to come. (The most recent edition came from [amazon text=Dark Horse Comics in 2007&asin=1595822003], and filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro owns many of the original drawings. It’s overdue for a reprinting.)

Wrightson drew a graphic novel adaptation of [amazon text=Stephen King’s Creepshow&asin=0452253802] in 1983 as well. More in line with his early work, it made a splash in mainstream bookstores at a time when trade paperbacks and graphic novels were still a bit of a novelty. More importantly, it led to a fruitful series of collaborations with King – first, illustrating Stephen King’s first calendar, [amazon text=Cycle of the Werewolf&asin=0451822196] (now collected as a regular trade), then doing a series of paintings for King’s expanded edition of [amazon text=The Stand&asin=B007OYVB76] and the fifth novel in The Dark Tower series, [amazon text=The Wolves of Calla&asin=141651693X].

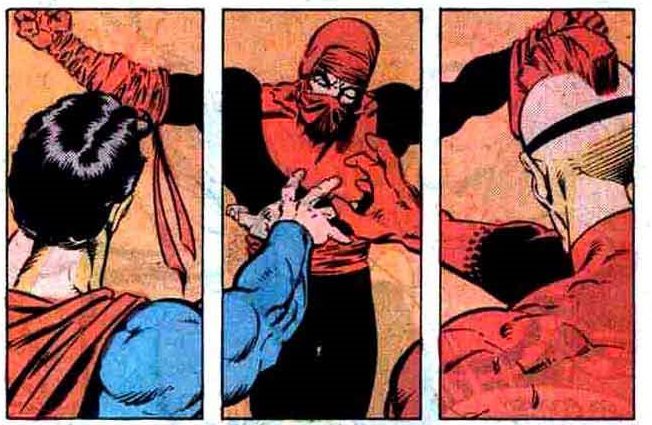

Teaming with Jim Starlin, another unique comics voice, Wrightson made a brief space for himself as a regular superhero comics artist. Except, of course, it was Wrightson, so when he played with the Big Two’s most popular toys, they seemed to be his own.

First with Starlin, he produced Heroes For Hope in 1985, an all-star comics jam to benefit victims of African famine. Featuring the X-Men, it marked the first of several such books over the years for various causes, providing a chance for comics fans and comics creators to give back. The two produced a similar title the next year for DC Comics, Heroes For Hunger, featuring Superman and Batman.

Something about dabbling with the main heroes inspired both artists, and their further collaborations for DC were simultaneously brilliant, melancholy, dark, and resonant. They also did a graphic novel for Marvel featuring The Thing and The Hulk, but it didn’t have quite the long-lasting impact that [amazon text=Batman: The Cult&asin=0930289854] did.

Featuring an underground army of homeless (literally underground), The Cult gave Wrightson the opportunity to draw a Gotham City as idiosyncratic and as much his own as Frank Miller made it in The Dark Knight Returns. Wrightson’s Batman was lean and wiry, like most of his figures, and you could feel the sweat and the fear permeating the streets. Though some of The Cult was “borrowed” for Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises, that film can’t touch the impact of the four issue mini-series.

Wrightson also expanded to the full Justice League, collaborating with Starlin on [amazon text=The Weird&asin=1401216927]. Not as well known as The Cult, it’s a personal favorite that does a more interesting job of melding Starlin’s more cosmic interests with Wrightson’s earthier art. An extradimensional bodiless entity made of pure energy, the Weird fled to Earth to help stop an invasion from its own overlords. Possessing a recently deceased suburban father, the alien had to recruit the Justice League to defend the planet while wrestling with strange emotions and memories of his host body’s life.

It’s the rare superhero story that wrestles with grief and the ineffable, sometimes painful, joy of being alive, and only an artist of Wrightson’s sensibility could have given it the right spark. It’s only fitting that The Weird sacrificed himself at the end, and though he has reappeared in this century, without Wrightson, he has little traction in fans’ hearts.

Wrightson, however, does. He didn’t continue much with superheroes, returning instead to his first love, horror. Ill health even kept him from a Swamp Thing revival. One of a kind, he leaves a great legacy in comics, inspiring artists as diverse in style as Mike Mignola and Kelley Jones, who did draw that revival of Swamp Thing. No doubt Wrightson will continue inspiring as new young artists discover his work.