When C-3PO appears onscreen in a Star Wars movie, he’s met with affection as part of a comic relief duo. Usually vaguely bumbling, he’s the character most likely to throw cartoonish sweat beads off his head in a panic, if he could sweat. But isn’t it odd that we even automatically call C-3PO a he? For “he” is a droid, a mechanical creation of circuits, metal, and programming.

From time to time watching Lucasfilm’s epic science fantasy films, there’s a nagging thought that comes to mind — if these droids have personalities, even droids whose lines we can’t understand like R2-D2 and BB-8, aren’t they kind of alive? In A New Hope, we even cringe watching Jawas torture a screaming droid. Or is it, as I am often accused, that I’m thinking too deeply, wondering too much about what should just be entertainment?

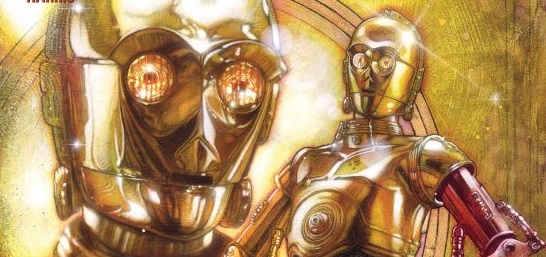

This is why Marvel Comics’ C-3PO unexpectedly turns out to be almost brilliant. It was obviously up to something, with a creative team of James Robinson and Tony Harris. But when the announcement of this book came, “the story of C-3PO’s red arm” — an almost throwaway joke in the movie — seemed like this was just going to be a funny little story. Robinson even plays with our expectations by calling it “The Phantom Limb,” as if we’re playing with The Phantom Menace.

But that’s what we call subverting our expectations.

Instead, we’re thrown into the midst of a mission on the brink of failing. A ship has crashed, and the only survivors, if we can call them that, are a group of droids. By default, they’re being led by C-3PO, ostensibly because as a protocol droid, he might have the most advanced programming. Certainly, he can best communicate in the varying levels of languages the others have.

But this group is like a posse in the old frontier sense. One of the droids works for The First Order, and somewhere in his data banks (possibly) is the location of an imprisoned Admiral Ackbar. As these droids make their way across a hostile (and downright frightening) landscape, they ponder right and wrong, and their place in it. Can any of them be considered “good” or “bad” when they’re simply a matter of programming that can be erased and redone?

Threepio gets ruminative, and has flashes of old programming from before the rebellion. Droids demonstrate courage — or is it just programming? — and we have to start wondering how different from us are they supposed to be? Or how different are we from them?

Robinson challenges us. Whether it’s reuniting with his sometime [amazon text=Starman&asin=1401216994] collaborator Harris, or that [amazon text=Airboy&asin=1632155435] really did help him purge something, this is the writer at his best. And he’s brought out something new in Harris as well.

The artist grunges up his style a bit, giving it shading and edges that recall Heavy Metal artist [amazon text=Richard Corben&asin=1595829199]. It fits the story of droids battling harsh elements to simply survive, and heightens the tension underlying Robinson’s philosophical concerns. C-3PO doesn’t quite look like any of the other Star Wars books from this era of Marvel; further, “The Phantom Limb” also could change the way you look at the golden droid.

This is why books and comics can fill an important gap for Star Wars fans. The movies have much higher financial stakes, and so do have to be broader, more swashbuckling adventures that admittedly can feel a bit repetitive. At this point, the films are comfort food, and for the majority of fans, that’s really enough and there’s nothing wrong with that. But every now and then creators can poke in the darker corners and come up with something that’s a little different, a little meatier (or more fibrous if you prefer). It’s just surprising and welcome that it was C-3PO that reminded me of that.