When I was 7 years old, one of my best friends had his grandfather living with the family. All the kids called him “Grampy,” though I would hear my parents talking about “Mr. Tanaka,” and eventually I figured out that’s who they meant. He seemed ancient to me, though he was probably in his early 60s, and he always found a reason to smile at the kids who gathered at the house.

Most days after school Grampy would load a few of his grandson’s friends into his Winnebago and make the 1/2 mile drive to 7-11 to get Slurpees and those formative DC Comics’ collectible cups. Sometimes his other grandchildren would be there, too, and I’d like to think he loved having so much life in that house. His daughter must have, or we probably wouldn’t have been hanging out there.

And then we all got older, and found different friends, though our parents stayed close. By the time I got to high school, it had been years since I had seen “Grampy.” One night, I was telling my parents that I had read about the Japanese internment camps in History class, only vaguely aware of [amazon text=Farewell to Manzanar&asin=1328742113], and it’s a point that George Takei makes in his memoir: we can’t learn from the past if we aren’t taught it. Sometime later, my mother told me that Mr. Tanaka had been in a camp, as had all his children. His wife had died there.

My mind was blown, and the point of long-windedly getting to George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy is that I couldn’t pick that book up without thinking of Mr. Tanaka, of Grampy, and of how little I understood of the pain and suffering his family had endured and I was an ignorant little kid who just wanted Slurpee cups.

I never talked to him about it. I never talked to his daughter about it, even though she and my mother were best friends until the day she died. Knowing how easily I stayed ignorant, it fuels my outrage at what’s going on today. And if I were to meet George Takei, I could only say “I’m sorry.”

Working with Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and artist Harmony Becker, Takei has adapted his memories, speeches, and his life into a stirring memoir of his childhood, offset with the strength and success he has had in his professional life. There are heroes (his father) and villains, but mostly humans, as Takei and his co-creatives struggle with the question of how so many can believe the only thing we have to fear is fear itself and yet be so afraid.

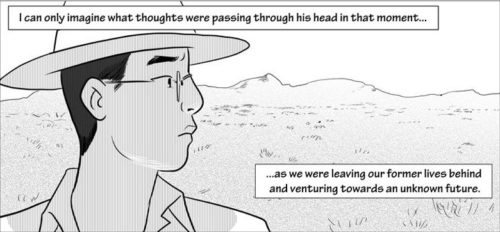

Takei opens on his childhood, the morning his family’s life was turned upside down. He also jumps around a bit in time, reminding us that this sleepy child George would grow up to be a successful actor, activist, and yes, an icon. Later in the book, he acknowledges that several hands lifted him up there. But the main drive of the book is his time in the camps, finding both confusion and joy in a dark time. Eisinger and Scott interweave flashes of George as a young man, adding layers of meaning to his memory, and angry with the father he sees as complacent. Even that layer, though, is seen through the lens of the man now, understanding so much more and guiding us to that same point.

With that understanding, Takei can both briefly sketch family history and lay out the dots leading to the infamous Executive Order 9066. There’s fear everywhere after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and that fear may have corrupted some people who knew better. But there were also plenty of people who swiftly let their bigotries run wild — and if it seems that Takei still can’t make up his mind over where the Roosevelts fell in that, he at least reminds us that even the best of us are flawed.

With a slightly soft cartoony style, Becker expertly captures the Takei family bond. While George and his siblings have the over-excited innocence of children, his parents visibly wear masks of reassurance over their worry. As its partly a childhood reminiscence, it’s easy to get caught up in the child George’s perspective, and get a little delight in his antics. But ugliness is never far beneath the surface, from the bigotry of soldiers and white citizens, to the understandable fear and anger of fellow Japanese-Americans in the camps.

Spoiler: just because the war ended, doesn’t mean that ugliness went away. There’s so much more to what went on during World War II in our treatment of Japanese-Americans than two or three sentences can convey. And we’re not left off the hook by this book — it’s not the distant past, it’s not “never again.” The saddest realization reading this is that Takei could stand with Presidents Reagan, Clinton, Bush, and Obama as justice slowly turned, and that our current incarceration was in place long enough to be included in this story. If you’re upset about current events, they didn’t just happen — they were building in plain sight.

As Takei notes, it’s slow moving toward justice, but we must — reading histories like this (along with publisher Top Shelf’s other [amazon text=civil rights graphic narrative&asin=1603093958] March), remembering what they tell us, and then standing up when it starts happening again. We can be good, but flawed. This nation may still be the best system on Earth, but we need to be aware, educated, and strong to make it work.

There’s little more to say than They Called Us Enemy reminds us of how complex we all are, but I also can’t quite shake the words of Walt Kelly’s Pogo — “we have met the enemy, and he is us.”