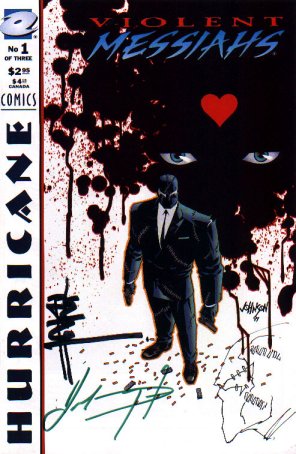

Yesterday, in part one of our interview, husband and wife team Bill O’Neill and Jan Utstein-O’Neill talked about how they forged a publishing company that has produced a critical and fan favorite. Starting in the mind of O’Neill and handed off to writer Joshua M. Dysart and artist Tone Rodriguez, that book, Violent Messiahs, is about to launch into a new story arc next week.

Derek McCaw: Bill, as co-creator of Violent Messiahs, and part of the management of Hurricane, you’re kind of in the back seat as far as the actual book goes. How does it feel to have this thing you created run off with Tony and Josh?

Bill: I don’t have a problem with it. I’m essentially, at least up until now, the idea guy. I’m finally starting to branch out into actually writing, but I’m more or less an idea guy. I came up with the initial premise of Violent Messiahs, the original premise for Chassis. I sort of bang things together and create something.

Like I said, we brought Josh on board to be the writer, and he just added so much we gave him co-creator credit, and Tony’s art is just so phenomenal. I sort of became a third wheel. They were doing fine without me; they really didn’t need too much of my input. I’m confident in what they’re doing, and pretty much let them do what they want.

Jan: The project really took on a life of its own, once it came into the realm of Tone and Josh. It also became a different animal than it was when it was Bill and Josh doing it. It’s kind of like an evolution.

Bill: My artwork I was trying to do was sort of a cartoon film noir style, and Tony’s is what I like to refer to as hyper-realistic. It’s just so detailed and so gritty. I’ve just been happy with what they were doing, and the fan response has been so strong. That gave me the confidence; I don’t really need to meddle in too much. Plus you get a third opinion in there, you just start bumping heads.

DM: Is the storyline sort of what you had in mind?

Bill: Oh, yeah, yeah. Especially for the first story arc. The Image Comics version was basically what we planned way back in ’97. Other than Josh getting to flesh it out and stuff like that. Back then, back in ’97, doing the black and white I had a little more input into the story per se, because I was drawing it and all that.

But now with the second story arc, other than me providing the name of the next vigilante character, Scalpel, it’s all theirs.

DM: How has the critical acclaim for Violent Messiahs changed things for Hurricane Entertainment?

Bill: I don’t know. Since I’ve become emotionally distant from the property, not really working on it other than an occasional drawing or something, I don’t really feel the acclaim. Other than I publish it. I feel more from a business end that we’re publishing a book that a lot of people like. Which ain’t bad. It’s quite stunning, actually. All of the reviews have been positive; we haven’t received one that’s like, “god, this is awful” type of abuse. At least for the first story arc. We’ll see how it goes for the second story arc; it hasn’t come out yet. Hopefully, the reviews will still be good.

DM: What can you tell me about that? What’s going on in Lamenting Pain? The first arc seemed so complete.

Bill: From my point of view, it’s a sequel. Hopefully a sequel more like The Godfather films rather than Smokey and the Bandit, Part Two. Hopefully it’s a good sequel.

Citizen Pain will be returning, but I don’t want to say how. Josh has come up with a clever way of bringing him back. Very cool. It involves Scalpel, the new vigilante character introduced in the story arc, who is completely obsessed with the vision, image, and existence of Citizen Pain. She’s just nuts about him, the ultimate groupie. She’s got a shrine and the whole thing. She ends up pursuing Sherry Major (the detective heroine of the first story arc), because according to the press, and what she knows she’s learned from the press, Sherry is one of the few people to ever actually come in contact with him.

Scalpel starts to pursue her, trying to get information out of Sherry about where is Pain. So we’ve built some sort of psychotic love story, love triangle. Scalpel loves Pain, Pain loves Sherry, and Sherry hates everybody.

That’s our twisted love story.

DM: Do you think there’s still a good mystique around Citizen Pain? That’s one thing a little jarring in the first arc, learning so much about him…unless it’s not Job coming back…

Bill: I won’t say anything about that. I would say no, that there’s still a lot of mystique. Actually we sort of had a business/art clash over whether we were going to bring Pain back, because he’s big…in this industry, he’s become an iconic visual in a way, to a large bunch of people. He’s got the potential of becoming iconic.

I never really wanted to get rid of him. I wanted to downplay him for other story arcs and then bring him back. We had a sort of creative meeting of the minds. We want him to come back, but we need to do something clever with it.

It’s a great balancing act, because all the fans really do dig Citizen Pain. But then we don’t want to insult them, either, by having him come back, to make it false story telling.

We’ve got a way where he will appear again.

Jan: You don’t really need to say anything more than that.

DM: It sounds more like in the aftermath of Citizen Pain, he’s more of a presence than an actuality. Do you think the real world media would be clever enough to call someone like that Citizen Pain?

Both laugh.

Bill: Yeah, I was pretty happy with those names. “Those are cool, put a line under those!” To that extent, I’m proud of what I added to it, because if I hadn’t produced those names, that conjure up interesting things in people’s imaginations…Josh has such a brilliant imagination. I’m glad I provided an interesting enough seed for him to wrap real cool ideas around. I feel really good about that. I came up with some additional concepts like that.

Jan: You were asking about the unmasking of Pain so early in the series. One of the initial ideas of the series was to take the cliches and twist those, and present them in a way that is more realistic. As opposed to the way the world would react to a vigilante. As Bill often says, if Batman was real, the police would be after him. They wouldn’t be working with him. By taking the mask off, we’re also doing something that is atypical for the comic book world. It’s not the only reason it was done, but we didn’t want him to become a typical character where for years you don’t know what he is and then maybe ten years down the line you take his mask off. We wanted to bring him from this vigilante character and bring another level to him early on. Josh decided that the best way to do that was to unmask him. I think we unmask him in #6.

Bill: I guess we broke comic book tradition and laws. If you’ve got a masked character like that, and you’re playing up the mystery of him, you have to continue to play up the mystery of what’s behind the mask. You get very jumbled origins like Wolverine, which they finally sorted out.

DM: No they didn’t. They sorted out my eighteen bucks.

Jan: I think that the moment that he actually gets unmasked, he was a monster up until then. Suddenly, in an instant, he’s humanized. For the themes of the story, that’s very important. The struggle between creator and created, the Frankenstein themes running through there. Knowing that he’s actually flesh and blood is very important to the story.

Bill: He’s very much like Frankenstein, in being both a tragic hero and a tragic villain.

DM: And very visually, as well, with the patchwork and the stitches.

Bill: I came up with the initial design of the character, and I hadn’t really thought of it that way. As a Frankenstein visual. My logic was, I was thinking more logical than philosophical. He’s just this really big guy, and he wasn’t leading a life where he could just wander into Barney’s and buy a suit, so he ends up stitching one together.

When we brought Josh on board, and he saw things in the visuals that I hadn’t considered. He sort of turned it into a Frankenstein motif, that I hadn’t initially thought of.

Our meeting had to be delayed a couple of hours, as Jan had been up all night putting together sample packets of Lamenting Pain #1. We talked a bit about the joys and frustrations of being a small studio.

DM: This is really interesting to me; you’ve got national distribution, putting out a slick book, people see it on the stands, you’re in Wizard, and yet you’re basically working out of your apartment. It’s the dream of desktop publishing come true.

Jan: Basically. I wear a lot of hats. If it wasn’t for the age of the computer, if I didn’t have a background in desktop publishing, we wouldn’t be able to do this.

The comic book industry is still pretty tight. Even with a successful book, there’s not a lot of dollars.

Bill: The profit margin is pretty thin. Even when you’re doing well, there’s not a lot of money coming in.

DM: Which leaves the question: why do this? What is it about comics?

Bill: I have no other skills. I’m not a rocket scientist, I can’t fix a TV. Since I always had an interest in comic books and Jan comes from a film world and theater, from different angles we’ve always had this storytelling urge in us. In one form or another, different variations.

When I exposed Jan to the world of comic books she found it intriguing and entertaining.

Jan: Really quick, I came from a background in theater. I was a set designer, and moved on from that to be a production designer in film (according to the Internet Movie Database, Jan worked on the horror classic Pumpkinhead) and then a producer in film. And then on to 3D animation and so on so forth.

For me, I’ve always been a part of telling a story. But in film, to tell a story you need a lot of people and you also need a lot of money. You need a lot of resources. The beauty of a comic book is you can tell a story, and you can do it in a way that’s…yours.

Bill: Ever since I was a kid, I was drawing my own comic books.

Jan: You can make your own world. You can control your world. You can bring your world to the public the way you want to do it, without having a lot of resources.