In Justice League #45, Darkseid, the evil ruler of Apokolips and dark god in the DC Universe, was killed by the Anti-Monitor. In a last bid to save himself, the dark god summoned the Black Racer, the avatar of Death itself, and it merged with The Flash, Barry Allen, turning him into the God of Death. All of the Justice League had made it to Apokolips because Batman had chosen to sit in the Mobius Chair, an omniscient flying piece of furniture that transformed Bruce Wayne into the God of Knowledge.

With the old gods all gone, the Wizard Shazam had to make alliances with new gods in order to keep Billy Batson from reverting to his 13 year old self., making “Shazam” (who will always be Captain Marvel to some of us) into the God of Gods. Superman fell into the fires of Apokolips, emerging as the God of Strength, and Green Lantern, naturally, was on track to become the God of Light.

Each of these five members of a super pantheon received one-shot issues that Geoff Johns’ epic Justice League story barely justified. But editorially, the stories were an attempt to throw the heroes into stark relief, doing as much to define who they are to a casual reader as could be done. Not that DC really has any casual readers left, and if you’re a fan of Batman or The Flash in particular right now, you’re better served by something like Batman and Robin Eternal or The Flash Season Zero that DC publishes to tie in to the hit CW series.

The aspects of the heroes amplified by the Darkseid War more often than not show how fundamentally far from their conceptions they have become in the New 52. In a couple of cases, the stories even rewrite iconic moments from 20th century comics. But maybe I should focus on the ones that get it right.

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD

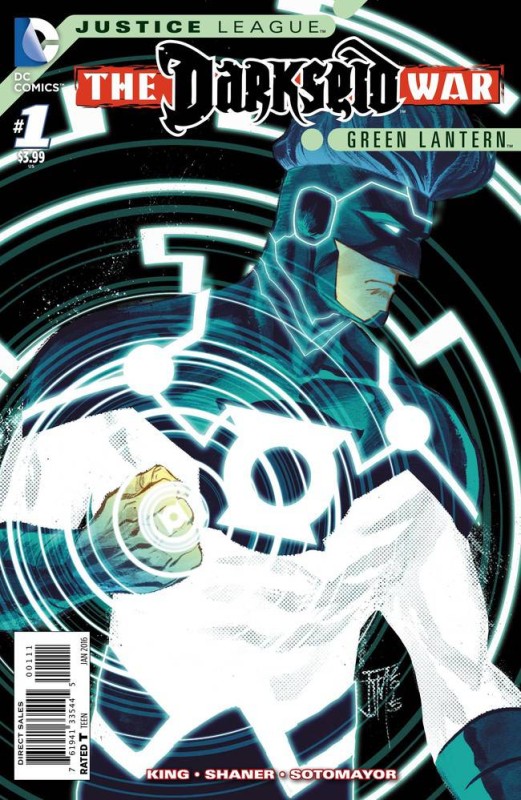

Since the 80s, no super epic worth its salt can be complete without an assault on Oa taking down the Green Lantern Corps. And though Tom King wrote the Green Lantern one-shot, “Darkseid War” writer Geoff Johns’ influence cannot be discounted, as he likely set the parameters of the stories, and has spent a good chunk of his professional comics career rehabilitating Hal Jordan. In Justice League, Batman dismisses Hal with the knowledge that the man has failed time and time again; it’s the ring that’s the hero. (A facile reading of Green Lantern mythos, of course, but Batman has always been a weak spot in Johns’ writing — the Dark Knight is more the God of Jerks, and when Johns writes him, always hates Hal Jordan.)

In the one-shot, Hal travels to Oa, where Parademons have converged seeking to merge their Apokolips technology “Mother Box” with the Green Lantern Battery. By the time Hal arrives, all the Corps have been slaughtered and revived as Parademons themselves. None of them had the will to accept the merger and become the new god that the Parademons seek to replace Darkseid.

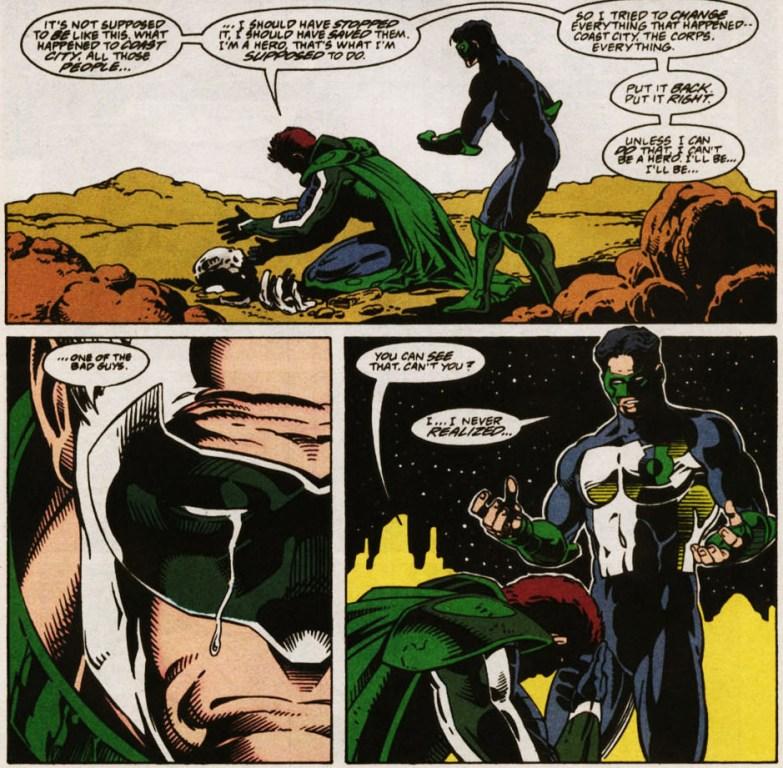

Hal, of course, has the will. (Where are the good New Gods such as Lightray in this? I skipped the big Green Lantern/New Gods crossover, Godhead.) The “greatest Lantern of them all” becomes the God of Light, reenacting and reversing the stain of his actions in the 90s, pre-Geoff Johns, when he sought ultimate power, killed all the Corps himself, and became the villain Parallax. Sure, that’s no longer part of the continuity, but it’s still in readers’ heads.

This time around, after restoring everyone to life (something Parallax didn’t do), Hal realizes that the key to ultimate triumph isn’t in accepting godhood, but in accepting humanity and his own innate heroism. He will be the redemptive force that saves Batman back in the pages of Justice League. It gets to the heart of why old DC fans are old DC fans: because we liked reading about heroes. They can be flawed and make mistakes, but they have to be good. Silver Age DC Heroes are the people we’d like to think we’d be if we got a magic ring or a magic word. And while the week before Tom King had given us a warped view of humanity in Marvel’s The Vision, a stranger among humans, he uses Hal Jordan, the stranger among aliens, to say something nice about us. Or at least Hal Jordan.

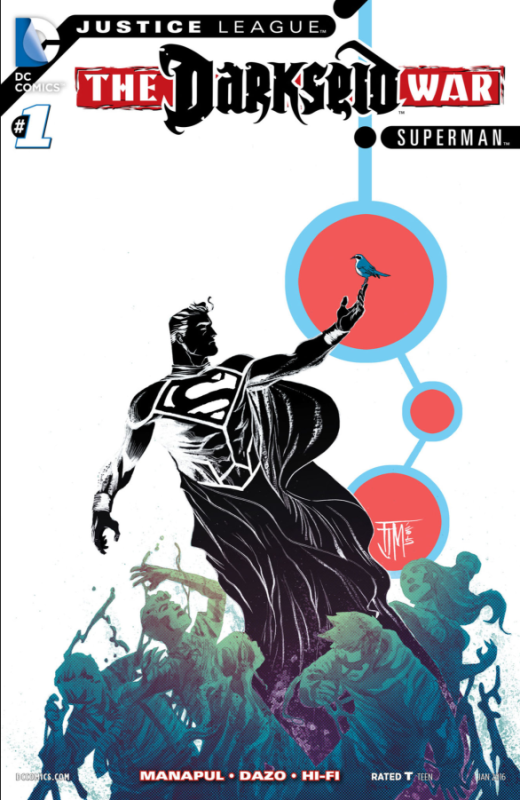

And I’ll take it, because it’s the strongest definition of the hero in these one-shots. Superman comes close, though he spends most of his one-shot being a hyper-exaggerated version of the bad Superman in Superman III. (Geoff Johns, by the way, got his start working for Superman the Movie director Richard Donner, who was famously fired from the franchise mid-Superman II. More reaction/repudiation of the past?)

Despite an infusion of too much Apokoliptian solar power, Superman is literally a negative of himself. He still believes that he serves on the side of good, but places himself so far above humanity that “good” can only be drawn in the big picture. Eventually he realizes that it’s the tiny details of humanity that makes him who he is, though the story ends with the negative energy still largely in control.

Writer Francis Manapul brings out a great detail about Superman in Metropolis: he frequents a certain diner because the owner treats him like everybody else, not like Superman. (Never mind that Clark Kent could get the same service.) Every now and then, it’s Superman who has to be treated like an ordinary joe as he sits down and orders a piece of pie, no doubt reminding him of Ma Kent’s home cooking. Nothing as American as apple pie, right? Except maybe to be from Kansas.

So those two heroes are basically the ones we’ve known most of our lives. Don’t get me wrong; they’re all still recognizable, but The Flash and Batman end up repudiating key good moments in their pasts. It’s probably more annoying in the case of The Flash. Before Johns had influenced the entire DC Universe and only ran The Flash, he had pitted Wally West against The Black Racer in a kind of fun story.

Johns hadn’t figured out how to bring Barry Allen back from the dead yet. At the time, he was a hero who had willingly sacrificed himself to save all of reality and whose sacrifice inspired his nephew Wally to be an even better hero.

When Johns restored Barry to life, he had also added a bit of backstory that had him haunted by his mother’s death, which led to Flashpoint, a bizarre rewriting of the DC Universe into a much darker timeline, that also served to launch The New 52, the continuity we are essentially reading now. Granted, after decades of stories, the board has to be cleared for new takes, new writers, and new readers. Even characters like Sherlock Holmes get writers adding new takes on old stories, updating the characters, and creating new and unforeseen adventures, and most people seem fine with that. What is SPECTRE but the culmination of a complete reboot of James Bond?

But the key thing about Barry Allen isn’t so much that he embraced death, but that as a bright shining hero, he knew he had to save the world and did it. He could be angry at death, he could feel sorrow at its loss, but in this one-shot, he’s afraid of death. Afraid of death? THIS far into his career?

He may not remember the reality before Flashpoint. Like Crisis on Infinite Earths, it’s an event/story that most writers prefer to acknowledge happen and then try to distract you with jingling shiny objects over to the left, so it’s undefined. But the weakness in this story is that he’s shown as still driven by an unwillingness to confront the reality of his mother’s death. Even the CW show wrapped that up at the end of Season One, with occasional CW backsliding for melodramatic purposes.

It’s not even unwillingness; it is flat-out stated as fear. It’s a defining character trait being brought up to serve a plot point for a one-shot that didn’t really need to exist (the main Justice League story is really good and barreling along quite nicely on its own). It probably won’t matter two years from now, except at family gatherings. (“Hey, Barry, do you remember that one time you were Death?”)

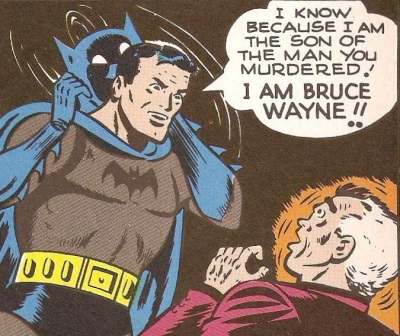

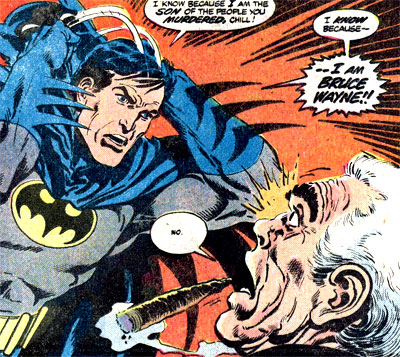

But first, in the midst of all this madness, DC Comics takes the opportunity to rewrite a classic Batman story — a defining moment in the 40s by the great Bill Finger and probably one of the few such defining moments actually drawn by Bob Kane. (It’s murky, but possible.) It’s the moment an adult Batman confronts the killer of his parents, Joe Chill.

Over the years, DC has gone back and forth over this. In the 90s, editorial flat-out stated in Zero Hour that Bruce Wayne never knew who killed his parents, reasoning then that every criminal could stand-in for the killer. It was wrongheaded then, and wrongheaded now. Batman doesn’t fight crime because he’s trying to find his parents’ killer; he fights crime because he’s trying to keep it from happening to other people.

The point of Batman’s taking the seat of the God of Knowledge is, obviously, that it’s his humanity that needs to be emphasized. Over in the main Batman books, with Jim Gordon in Bat-armor, that’s being proven quite nicely. For whatever reason, Bruce Wayne is spending time doing social good and feeding his own soul. None of that is reflected in Justice League; this likely fits before Endgame in continuity.

For here, he’s lost his soul completely. Jim Gordon complains about it as Batman has turned Gotham City into an Orwellian nightmare: not completely crime-free yet, but getting there. And the Mobius Chair feeds on him. How does he not get carbuncles? THIS is the moment he decides to confront his parents’ killer.

Again, as with The Flash, I have to ask — this late in his career? The problem with making Joe Chill a plot point is that Batman is a detective. In an era where we pay more attention to huge arcs over cool individual stories, and Batman is a tentpole action star for Warner Brothers, we’ve kind of lost that. Confronting Joe Chill was a great moment in being a detective — and a great moment in comics when adults weren’t paying as much attention. A lot of 1940s comics stories have lost their luster, but many of Bill Finger’s works still have impact.

Take this moment. Batman has tracked down Joe Chill, forces him to confess to the murder of Thomas and Martha Wayne, and then…

He leaves Chill with that knowledge — that this small-time crook created the city’s greatest scourge against crime. (And if that is Bob Kane’s art — Charles Paris is listed as inker — we should give him a little due as a draftsman, because that is an intense look on Bruce Wayne’s face — pain, anger, and excitement that this moment has come.) Let’s look at that moment recreated decades later:

The cigar has been added because Chill got rewritten as being part of a larger conspiracy, because, you know, it’s been decades since random crime has been allowed to actually be random crime in American storytelling. Everything has to happen for a reason.

In Finger’s original story, Chill fled, ran into some other criminals, and told them that he had created Batman. Off-panel, they actually beat him to death for it before realizing that they should have stopped to find out who he was. It’s a surprisingly sophisticated story about the cycle of violence, and the unthinkingness of cruelty. And, of course, Batman doesn’t stop being Batman.

He doesn’t in The Darkseid War: Batman, either, but it’s the Chair that has given him the knowledge, and the confrontation comes in a story that defuses Batman’s passion and anger because he’s spent the whole time being inhuman. Then, after confronting Chill, letting the knowledge of what he’s done sink in, he… wipes Chill’s memory of that knowledge. No consequences. Nothing that could be picked up later. Since the Mobius Chair gives Batman this ability, it’s literally Deus Ex Ikea.

It’s lost all its meaning.

As has Shazam.

Look, we all have to get over that for legal reasons, DC can’t publish a book about a character called Captain Marvel, except when they do. To avoid confusion with Marvel’s Captain Marvel, they changed Billy Batson to Shazam, made him a little more mystical, and, well, he’s always been difficult since [amazon text=the 1970s&asin=1401255388]. And though Fawcett’s version of Captain Marvel was once the top-selling comic in America, I do understand that the character has been hard to fit in with modern sensibilities. Except, again, when [amazon text=DC manages to do it&asin=1401209742].

It took a while to warm up to [amazon text=Geoff Johns’ and Gary Frank’s version&asin=1401246990], introduced in back-up stories in Justice League and opening the door for the character to be fully embraced by the DC Universe, if not by fandom. Johns, Jim Lee, and Dan DiDio have been rewriting the rules of magic in the DC Universe, and the wizard Shazam is now a much more inclusive figure who appears far more ancient Egyptian than he ever did before — and that’s a good thing.

This one-shot also makes the pantheon that powers Billy Batson more inclusive than a [amazon text=strange mix&asin=B009M4KT3I] of Greek and Roman gods plus one Hebrew king — but is it really a diverse group when you’re including H’ronmeer, the God of Fire from Mars? Delve deep into world religion — that would be cool. Grant Morrison just did a nice job with that in [amazon text=The Multiversity&asin=1401256821], and Neil Gaiman set the bar high with [amazon text=American Gods&asin=0380789035] and [amazon text=Anansi Boys&asin=0060515198].

That’s quibbling. Change it up — you’re in a fictional universe anyway, telling stories about a character who isn’t real. But to a lot of fans, he still means a lot. And this kid in the Justice League — he’s not the kid we know. He’s a jerk. He mouths off to every deity he encounters — granted, when faced with Darkseid’s father, he probably should in order to prove he’s brave. That one we can forgive. But he’s just in general an obnoxious adolescent and… yes, that’s possibly realistic. I’ll bet we all know a lot of obnoxious adolescents. We also know a lot of respectful ones, good and kind ones, the kind that Billy Batson used to be — and that includes every animated appearance up until The New 52 took hold.

Eh. It’s an old fan complaining. On the other hand, both Grant Morrison and Jeff Parker made the original character work — giving him a sense of kindness, of wonder, and fun. The original Captain Marvel is fun. Shazam? Not so much.

And that’s a shame, because over at Marvel, they’ve got a whole line of Spider-Men who have both modern sensibilities and a sense of fun. Those sell really well. Can we try making Shazam be fun? Please?

Let the heroes be who they were, because it worked. In some cases, they’ve lasted almost eighty years for a reason. Try to find that reason, and not just the trademark.