The comics industry has been rocked this weekend — and really, that’s not hyperbole — by the unexpected death of creator Darwyn Cooke. Friday morning came the announcement that he had been battling cancer and had entered palliative care, and by Friday night, word had gone around that Cooke had passed. Though members of the industry had received confirmation from Cooke’s family at that time, the official announcement was not made until Saturday morning.

But let us celebrate the work of Cooke, an astounding artist who brought life and joy to every page he created, whether as writing or drawing. His first professional impact came as a storyboard artist on Batman: The Animated Series, continuing on with Bruce Timm for Superman: The Animated Series, as well as working on Men In Black: The Animated Series. While working on Batman, he pitched a comics story to DC Comics, and after a couple of years of watching his star rise in Los Angeles, the company came back and accepted it.

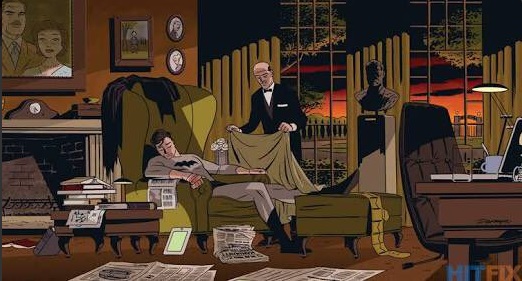

That story was Batman: Ego.

A deep psychological exploration of Batman, the book was critically acclaimed, and would lead to further work with DC. Cooke brought a unique style and energy to the DC Universe (though he always credited Jack Kirby as a major influence). With Selina’s Big Score, he cemented a look that seemed both a throwback to another time and perfectly timeless. That graphic novel would also foreshadow his most recent major work, the adaptations of Richard Stark’s Parker novels.

But first, Cooke would also redesign Catwoman for DC. Even Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises owes a debt to Darwyn Cooke. Though never explicitly called Catwoman, the costume for Anne Hathaway’s Selina Kyle was straight out of Cooke’s famous design, which has dominated for the character’s look in the 21st Century. In addition to Selina’s Big Score, Cooke collaborated with Ed Brubaker for several issues of Catwoman, placing her firmly in the category of cool crime comics.

DC also gave Cooke an issue of Solo, a great mini-series in which each issue was an artist’s showcase — short stories allowing the featured creator to run wild with whatever they wanted to do. It’s a high point.

As far as lasting impact on the DC legacy, Cooke created Justice League: The New Frontier. A retelling of the origins of the team set in the early sixties (a favorite milieu for Cooke), the story gave us a reality in which Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman had also been members of the Justice Society, and were the only heroes still operating after the government had disbanded the team. It was about new generations; it revitalized the legends of Green Lantern and Martian Manhunter. More importantly, it was a book about hope. (And it was adapted into a pretty effective animated movie.) Allegedly, it was also the only book from DC Comics that Watchmen writer Alan Moore enjoyed.

Years later, Cooke would give his famous interview decrying how superhero comics had lost their way. And though he continued working for DC, he devoted the lion’s share of his time to those adaptations of the Parker novels. Originally written by Donald E. Westlake as Richard Stark, the first volume, The Hunter, had been the inspiration for three films: Point Blank with Lee Marvin, Payback with Mel Gibson, and most recently Parker with Jason Statham. Predictably, it’s Cooke’s graphic novel that stays truest to the original book, both honoring the source while still making it inimitably Cooke. It won an Eisner.

Cooke took part in the controversial Before Watchmen project from DC Comics, a prequel to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ classic graphic novel Watchmen. As a concept, it sent Moore spitting a lot of rage, but he had to have appreciated Cooke’s contribution — a tale of the original superteam The Minutemen. He had found a way to restore brightness and hope from the Golden Age, injecting it into even one of the bleakest of superhero concepts.

There’s much more to Cooke’s creative legacy. He collaborated with many, and influenced many more.